Every year, a great number of delegates convenes at the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The representatives of nation states strive for mutual agreements for climate action. As climate change is a global problem, which just one country cannot tackle all by itself, such a coordinated approach on the international level is indispensable.

In this article, you get an overview of the contents of the framework convention on climate change, the structure of the multilateral climate negotiations and the most important milestones of the climate diplomacy so far. As a last point, an assessment of the international efforts for climate protection and against the negative impacts of climate change ensues.

History

In 1992, the international community adopted the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). At the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 154 nation states signed the document, which entered into force only in 1994.

Earlier, several important meetings of scientists have taken place. In 1979, the first scientific “World Climate Conference” passed off. In 1988, the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). With its assessment and special reports, the IPCC compiles the state-of-the-art knowledge, which provides the basis for political action. In the same year, political negotiations started, which finally resulted in the UNFCCC.

Contents

The objective of the UNFCCC is the “stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”. To achieve this target, the document emphasises the “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities” of countries. This is due to the diverse (inter alia financial) capacities depending on the economic power of the nation states and because of the differing historical responsibilities for climate change depending on past greenhouse gas emissions.

These – sometimes obscure – formulaic compromises mask the fact that a framework convention defines the underlying fundamentals and basic principles. The Parties to the Convention shall elaborate on the details only subsequently. This is the reason why every year the so-called COPs take place.

Procedure of negotiations

At the climate talks pertains the principle of consensus – all Parties to the Convention have to agree. This constitutes a major difficulty as there are by now 197 Parties with different interests and starting situations. However, to facilitate the proceedings, there are several negotiating groups – one of them is the European Union.

Most of the groups split into industrialised countries on the one hand and developing countries on the other hand. The Framework Convention of 1992 provides for such a binary division of countries and passes the primary responsibility to tackle climate change to industrialised countries. This is a major point of contention leading to criticism and difficult negotiations because the underlying economic and political realities have changed a lot ever since. Nevertheless, the nation states have already achieved various decisions and agreements, as the following photo series shows.

Milestones of the international climate negotiations

: COP30 Amazônia in Belém

The COP30 World Climate Conference will take place in Belém, Brazil, from November 10 to November 21, 2025.

On November 11, 2025, Environment Minister Thekla Walker and Secretary Wade Crowfoot signed a joint statement at COP30 in the presence of Governor Gavin Newsom and State Secretary Jochen Flasbarth to deepen the partnership between Baden-Württemberg and California. The statement builds on the Memorandum of Understanding that has been in place since 2018 and strengthens cooperation in the areas of environment, climate, and energy through concrete joint activities.

Download

Joint Statement on California and Baden-Württemberg Partnership [PDF; 11/25]

: COP29 in Baku

The world climate conference COP29 took place in Baku/Azerbaijan from November 11th to November 22nd, 2024.

World Climate Conference COP29 in Baku/Azerbaijan (in englischer Sprache)

: COP28 in Dubai

The world climate conference COP28 took place in Dubai from November 30th to December 12th, 2023. The main results of this year's COP were:

- “Global Stocktake” (GST): For the first time, a global inventory was created as to whether the greenhouse gas reductions promised so far are sufficient to achieve the 1.5° degree target and which “gaps” still need to be filled to achieve this. The result of the “Global Stocktake” was that humanity is heading towards an increase in the global average temperature of 2.1 to 2.8 degrees if all of the states’ current voluntary commitments are implemented. According to the final document, in order to further reduce global warming, a “comprehensive, rapid and sustainable reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions” of 43 percent by 2030 and 60 percent by 2035 compared to 2019 levels is required. By 2050, net carbon dioxide emissions should be zero (Number 27 in the final document).

- “Loss and Damage” compensation fund for poorer countries: So far, these countries have only received financial resources for adapting to the climate crisis and for projects to reduce emissions - but not for damage and losses. The fund is based at the World Bank for a transitional period. At the start of the conference, Germany and the United Arab Emirates each pledged 100 million dollar for the fund (as of December 12, 2023: a total of around 800 million dollar).

- Triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030

- Doubling energy efficiency by 2030

- Attempt to find a common position on ending the use of fossil fuels

Until the final declaration was passed, the last point was the main issue. It is an achievement that such wording was included in the final document. The call to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030 is also welcome. In the same period, energy efficiency is to be doubled.

: COP26 in Glasgow

The next COP will take place in Glasgow in October 2021, United Kingdom (postponement due to Corona virus). Until then, nation states shall present their new or updated NDCs. In Madrid at COP25, already 120 countries joined the “Climate Ambition Coalition” and announced to achieve climate neutrality or net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Moreover, 80 states pledged to upward revise their NDCs.

: COP25 in Madrid

The Spanish capital Madrid hosts COP25 in 2019. The focus of negotiations is on several points, on which countries could not find a compromise yet in Katowice one year before. These include the so-called market and cooperation mechanisms: The collaboration of nation states shall facilitate climate action and make efforts more efficient. However, this requires rules. For instance, it should not happen that both cooperating countries count the emission cuts towards their respective NDC. However, delegates were unable to resolve the issue and had to adjourn the negotiations.

Moreover, unavoidable losses and damages due to climate change are coming to the fore. For example, people can only adapt to sea level rise up to a certain point. Although the Paris Agreement explicitly excludes any liabilities or compensations, developing countries demand financial means to deal with climate-related losses and damages at COP25.

: COP24 in Katowice

Even though the Paris Agreement enters into force already in November 2016, it takes until COP24 in Katowice, Poland, in 2018 for the Parties to agree upon most of the details to give effect to the Paris Agreement. Common and consistent reporting requirements and transparency provisions now apply to all countries; only developing countries with low capacities obtain a certain degree of flexibility with respect to the guidelines. This way, efforts for climate protection, adaptation and climate finance shall become more transparent and comparable.

In addition, Parties conclude the Talanoa Dialogue, which the Fijian Presidency initiated one year ahead at COP23. The Talanoa Dialogue constitutes a first stocktake of collective climate efforts since adoption of the Paris Agreement and is supposed to help countries in revising and updating their NDCs. In the future, such a stocktaking event will take place every five years, which shall contribute together with the regularly adjusted NDCs to a continuous increase of collective climate ambition.

: COP21 in Paris

The French capital Paris hosts the largest diplomatic meeting in world history in 2015, the COP21 of the UNFCCC. For the first time, national representatives succeed in adopting a legally binding climate accord that applies to all countries. According to the Paris Agreement, the international community strives to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius and to pursue efforts to reach even 1.5 degrees Celsius. For this purpose, Parties aim to achieve a balance between emissions and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases.

However, countries determine themselves as part of their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) what they add to global efforts on climate action. Legally binding objectives for individual countries are not part of the agreement. In addition, delegates postpone the clarifications of details to later conferences. Baden-Württemberg supports reaching the Paris Agreement and establishes together with California the subnational climate leadership alliance Under2 Coalition.

: COP18 in Doha

Another year later in 2012, nation states agree at COP18 in Doha, Qatar, as part of the so-called Doha Amendment upon a second commitment period (Kyoto II), which will last from 2013 until 2020. This extension is rather symbolic, because it encompasses only 15 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions at the time. The United States of America never joined the Kyoto Protocol and Canada withdrew in the same year. Additionally, Japan, New Zealand and Russia refuse to enter into any new commitment. Per se, the Kyoto Protocol does not include any obligations for developing countries and emerging economies. As things stand today, the Doha Amendment has still not entered into force yet.

: COP17 in Durban

At COP17 in Durban, South Africa, the global community decides in 2011 to make another attempt to reach an international, legally binding climate agreement. This treaty shall apply to all Parties to the UNFCCC. For this purpose, the delegates establish the “Ad hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action” to broker a deal.

: COP16 in Cancun

One year later in 2010, Parties officially adopt the Copenhagen Accords at COP16 in Cancun, Mexico, with the so-called “Cancun Agreements”. In addition, they set the course for a bottom-up strategy: Prospectively, nation states shall communicate themselves what they can contribute to international climate action. Setting targets in a top-down fashion through tough negotiations shall no longer prevail – in that case, concerned and unwilling nation states can anyway object and veto.

: COP15 in Copenhagen

COP15 in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 2009 shall bring about success: Parties shall adopt a new agreement under the UNFCCC, which is supposed to take effect after expiration of the Kyoto Protocol. However, the negotiations prove very difficult and arduous; the whole conference is on the brink of collapse. In order to prevent complete failure, countries at least take note of a political accord. This accord is without any commitment, but it acknowledges the target to hold global warming below 2 degrees Celsius. Moreover, industrialised countries pledge to provide at least 100 billion US-Dollar climate finance per year by 2020 and the Parties establish the Green Climate Fund.

: COP13 in Bali

Ten years after the conference in Tokyo, national delegates debate at COP13 in Bali, Indonesia, in 2007 about the further procedure. They establish two negotiation tracks: The first track focuses on the continued obligations for industrialised countries. The second track centres around “long-term cooperation” which includes potential contributions from developing countries and emerging economies. Baden-Württemberg supports the negotiation positions of Germany and the European Union to enshrine legally binding commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions for all countries in a new agreement.

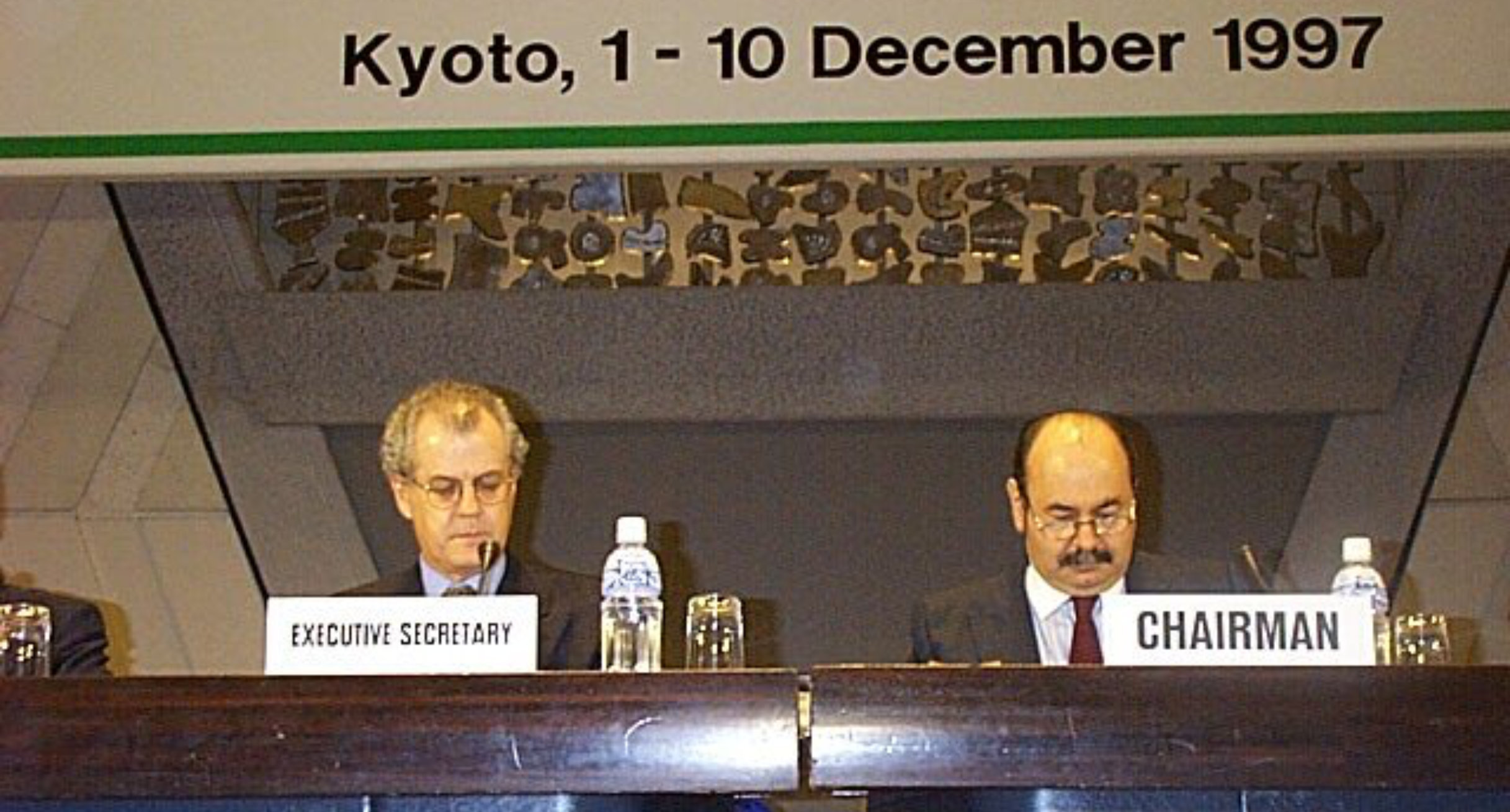

: COP3 in Kyoto

In 1997, Parties conclude the negotiations under the “Berlin Mandate” at COP3 in Kyoto, Japan: The so-called “Kyoto Protocol” obliges industrialised countries to cut down their greenhouse gas emissions. From 2008 to 2012, these countries shall reduce their emissions by 5.2 percent compared to 1990. However, the United States of America never join the Kyoto Protocol because developing countries are free of any restrictions. Only in 2005, the Kyoto Protocol enters into force, after enough industrialised countries have ratified the international agreement to satisfy the trigger.

: COP1 in Berlin

After the entry into force of the UNFCCC, the first Conference of the Parties (COP1) takes place in Berlin, Germany, in 1995. As Parties are not able to agree upon a different procedure, the consent principle applies to the negotiation according to the terms of reference. Moreover, negotiations under the so-called “Berlin Mandate” start to agree upon a Protocol in order to be able to achieve the objectives of the UNFCCC.

After more than three decades of international climate diplomacy, the issue of climate change as become even more pressing, more urgent and greater than before. Respectively, there is a lot of criticism: The proceedings under the UNFCCC only had a marginal impact on the development of greenhouse gas emissions so far. Several commentators conceived the negotiations to be inelastic and inflexible, partly due to the binary division of the world into industrialised and developing countries. The consent principle prevents far-reaching agreements, as nation states usually only agree upon the lowest common denominator. In addition, so far the negotiations mainly centred around the sharing of burdens, i.e. negatively connoted impacts on countries. Last but not least, some observers have accused the negotiations under the UNFCCC to be far away from the situation on the ground. There is no direct contact to the areas and people already affected by climate change.

However, delegate have achieved at least some progress, particularly when looking at emission data, reporting requirements and capacity building for developing countries. This progress constitutes an important foundation for future efforts. In addition, many commentators and negotiators value the international climate talks under the UNFCCC for their fair and inclusive character.

The public attention and media reporting at COPs also generates pressure to adopt effective strategies and measures. The Paris Agreement has also accommodated some of the long-standing points of criticism, as it has a hybrid character: Individual contributions by all nation states on the one hand follow consistent patterns and joint rules in order to provide transparency and comparability. In addition, peer pressure and high public expectations in times of aggravating climate changes play a decisive role in the new architecture of the Paris Agreement. Finally, it is hard to judge what the status quo would look like if there would be no UNFCCC as a coordinated international approach to tackle climate change.

The State of Baden-Württemberg advocates for an intensification of climate action, both within our State and internationally under the UNFCCC. With the subnational climate leadership alliance Under2 Coalition, Baden-Württemberg and other ambitious states and regions strive to contribute to positive results at the international negotiations on climate action and to lead by example.